The cobblestones of revolutionary Paris echo with more than just the clatter of wooden wheels and hurried footsteps—they resonate with the thunderous applause of readers who’ve discovered the intoxicating world of Revolutionary France in historical fiction. Like a perfectly aged Bordeaux (assuming you could afford one before the Revolution made such luxuries rather… problematic), these novels blend the intoxicating drama of political upheaval with the timeless human stories that make history breathe.

For those of us who’ve sailed the treacherous waters of historical fiction—whether through the pirate-infested seas of 1820s Hawai’i or the sultry streets of New Orleans—Revolutionary France offers an entirely different kind of adventure. Here, the danger doesn’t come from cutlass-wielding corsairs but from the razor-sharp blade of Madame Guillotine and the equally sharp tongues of Parisian society.

Picture this: cheering crowds gather along the cobbled streets of Paris, their voices rising above the rhythmic clang of the guillotine. The air is thick with fear, fervor, and the scent of change. This is Revolutionary France—an era as brutal as it is mesmerizing. In this article, we’ll explore why Revolutionary France in historical fiction continues to captivate readers, from classics like A Tale of Two Cities and The Scarlet Pimpernel to modern gems like A Place of Greater Safety. Whether you’re a historical fiction devotee or a curious newcomer, this 26-minute read is your guide into literary revolution.

- The Allure of Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

- Key Themes in Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

- Notable Authors and Their Revolutionary Masterpieces

- The Historical Accuracy Debate

- Writing Revolutionary France Historical Fiction: Challenges and Opportunities

- The Psychology of Revolutionary Characters

- Revolutionary France vs. Other Historical Fiction Settings

- Modern Relevance of Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

- Conclusion

- Essential Revolutionary France Historical Fiction: Top Recommendations

The Allure of Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

Why This Era Captivates Modern Readers

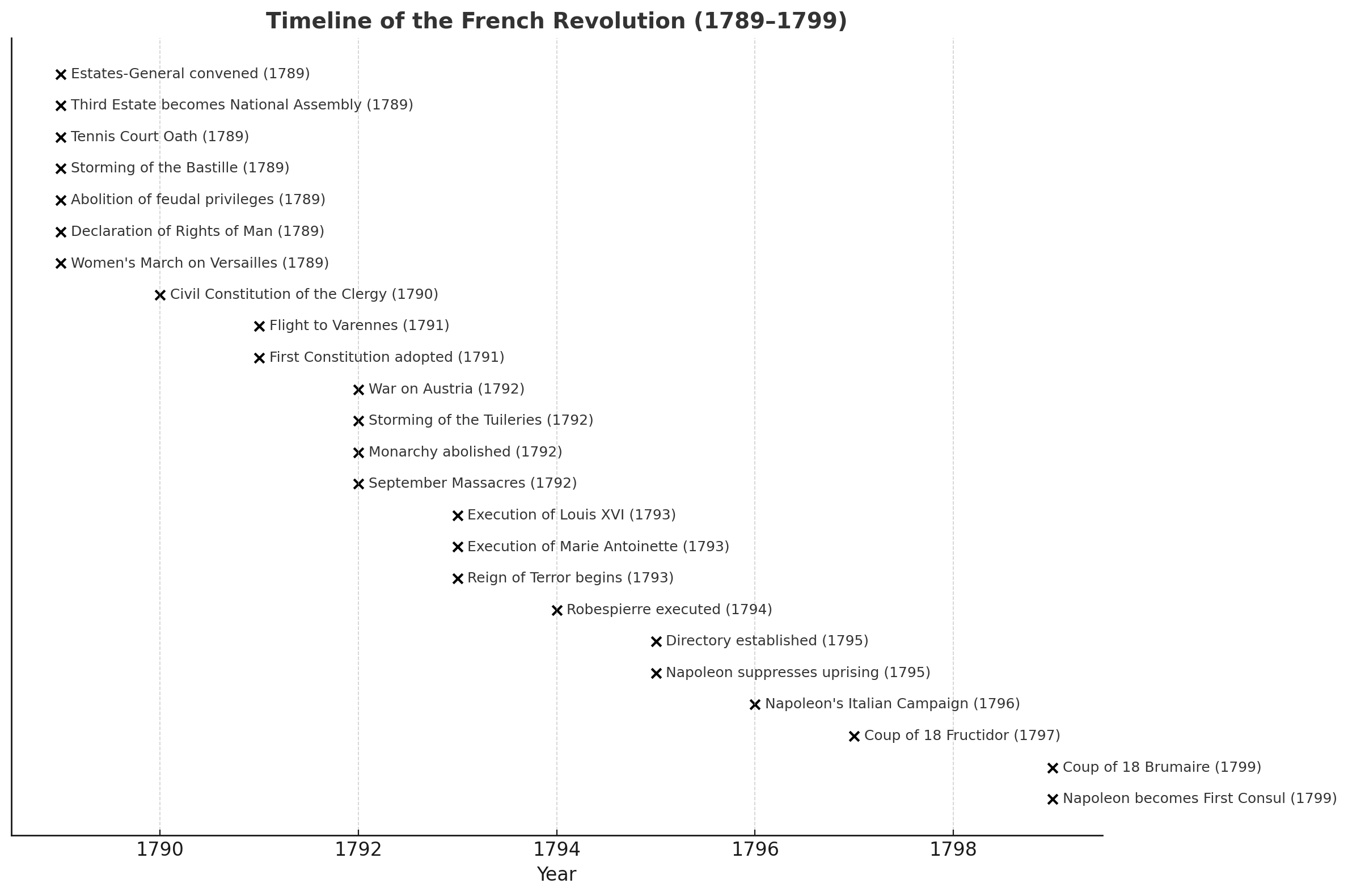

Revolutionary France historical fiction possesses an almost magnetic pull that draws readers into its tumultuous embrace. The period from 1789 to 1799 offers everything a historical fiction enthusiast could desire: political intrigue that would make Machiavelli weep with envy, romance that blooms amid the chaos of social upheaval, and characters whose moral complexities rival those of our beloved pirates and privateers.

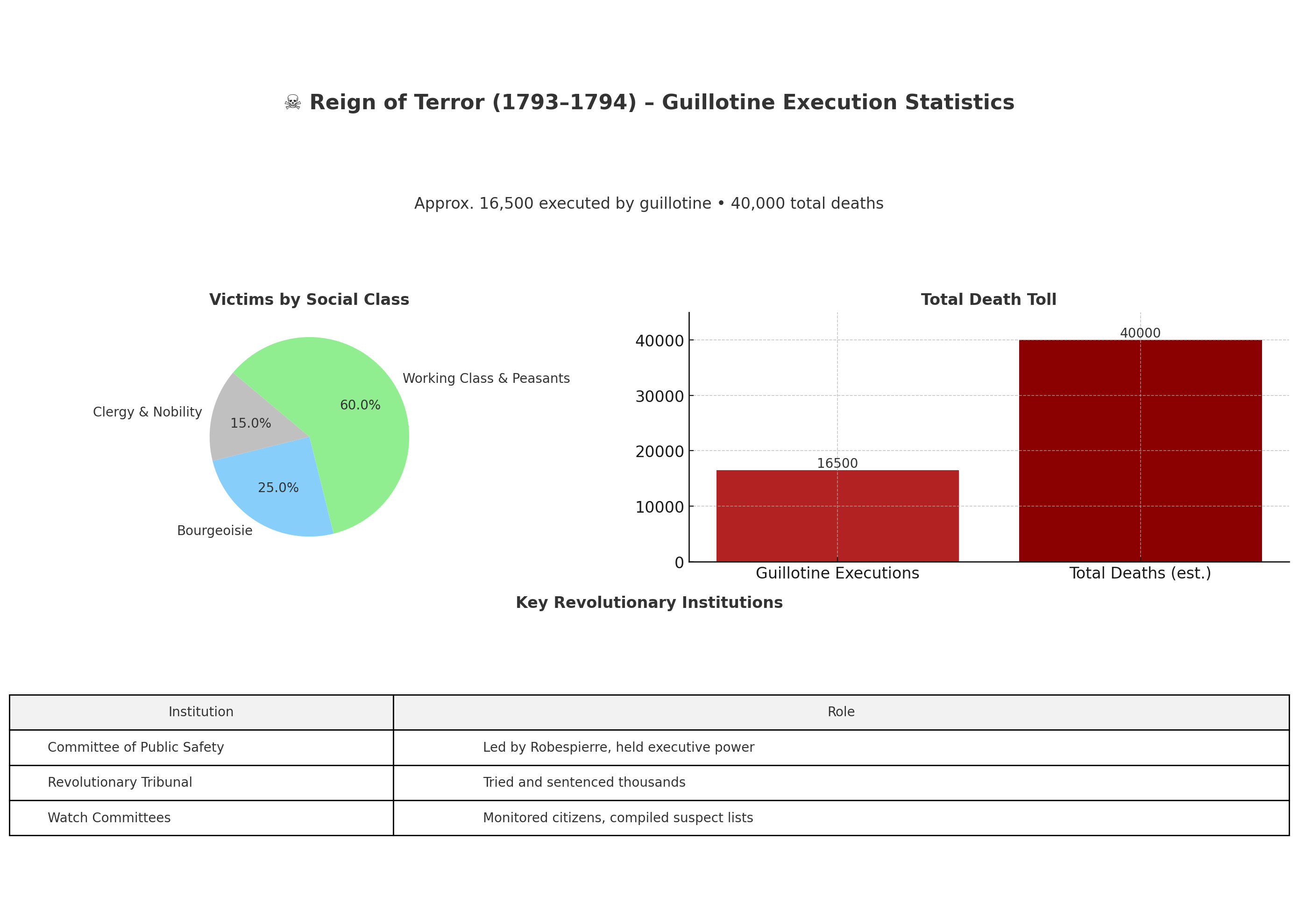

The French Revolution presents a fascinating paradox—a movement that began with noble ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité yet descended into the blood-soaked madness of the Reign of Terror. This duality creates the perfect storm for compelling storytelling, where heroes and villains often exchange roles faster than a Parisian crowd could shout “À la lanterne!”

“À la lanterne!” was a bloodthirsty rallying cry during the French Revolution that literally meant “To the lamppost!” It became a rallying cry that gained special meaning and status in Paris and France during the early phase of the French Revolution from the summer of 1789.

The phrase was essentially a call for immediate execution by hanging. Lamp posts served as instruments for mobs to perform improvised lynchings and executions in the streets of Paris. When angry crowds shouted “À la lanterne!” at someone, they were demanding that person be dragged to the nearest lamppost and hanged on the spot.

The most famous lamppost was located in the Place de Grève in front of the Hôtel de Ville, where in 1789 the crowd hanged Joseph-François Foulon de Doué, who was suspected of controlling grain supplies during food shortages.

The cry represented a cry for justice, as well as revenge. It was a cry for equality, but also of hate. The horrible mob violence of the early French Revolution was a result of a people downtrodden for far too long.

This wasn’t just empty rhetoric – it was a very real threat that resulted in summary executions throughout the early revolutionary period, as angry mobs took justice into their own hands using the convenient street furniture of Parisian lampposts as makeshift gallows.

Much like the morally ambiguous world of piracy, Revolutionary France challenges our modern sensibilities. Were the revolutionaries freedom fighters or bloodthirsty radicals? Was Marie Antoinette a frivolous queen deserving her fate or a tragic figure caught in history’s crosshairs? These questions provide the rich soil from which extraordinary historical fiction grows.

The Human Drama Behind the Headlines

Revolutionary France historical fiction excels at revealing the intimate human stories behind the grand historical narrative. While textbooks focus on dates and political movements, novels in this genre illuminate the baker’s wife who couldn’t afford bread, the aristocrat hiding in plain sight, or the idealistic young revolutionary whose dreams slowly curdled into nightmares.

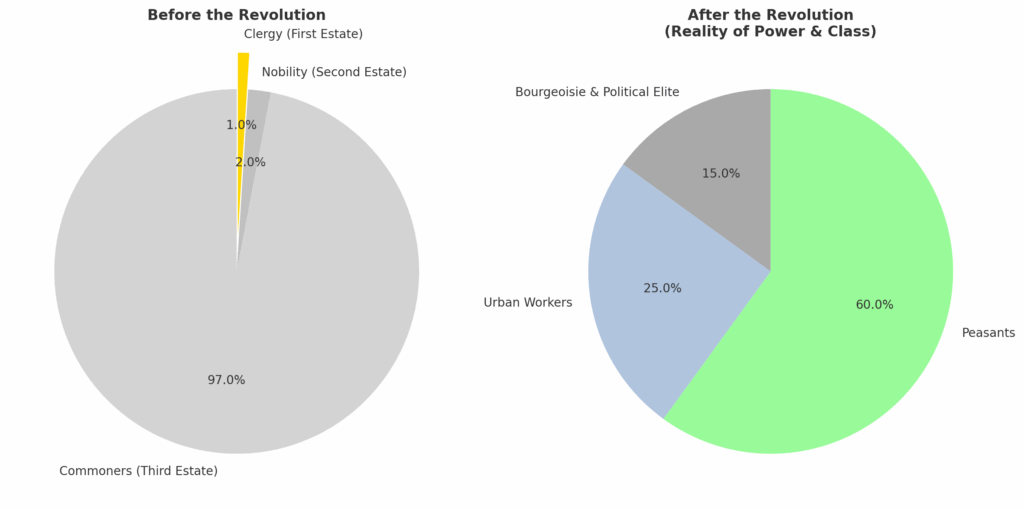

Consider the delicious irony: a period obsessed with equality produced some of history’s most unequal outcomes. The revolution that promised to eliminate class distinctions simply created new hierarchies—though admittedly, the new aristocracy of virtue proved just as fallible as the old aristocracy of birth. Historical fiction writers feast on such contradictions like revolutionaries at a confiscated château’s wine cellar.

Key Themes in Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

Love in the Time of Guillotines

Romance during the French Revolution carries a particular poignancy—after all, nothing says “till death do us part” quite like the very real possibility that death might part you tomorrow. Revolutionary France historical fiction often explores love stories that transcend class boundaries, political affiliations, and the ever-present threat of the scaffold.

These romantic narratives frequently feature star-crossed lovers from opposing sides of the revolutionary divide: the aristocratic lady and the passionate revolutionary, the moderate politician and the radical’s daughter, or the royalist spy and the republican officer. The tension between personal desire and political loyalty creates a delicious conflict that keeps readers turning pages faster than heads rolled during the Terror.

The period’s social upheaval also provided unprecedented opportunities for women to step beyond traditional roles—though often at considerable personal risk. Female characters in Revolutionary France historical fiction frequently navigate the treacherous waters between maintaining their femininity and surviving in an increasingly dangerous world.

The Price of Idealism

Revolutionary France historical fiction excels at exploring the corruption of noble ideals. Characters who begin as passionate believers in justice and equality often find themselves compromising their principles to survive—or worse, becoming the very monsters they sought to destroy. This theme resonates powerfully with modern readers who understand how quickly political movements can lose their way.

The revolution’s trajectory from hope to horror provides fertile ground for character development. Authors can trace the psychological journey of individuals caught in history’s maelstrom, showing how ordinary people become capable of extraordinary acts—both heroic and horrific.

Survival and Adaptation

Perhaps no theme in Revolutionary France historical fiction proves more compelling than the human capacity for adaptation. Characters must constantly reinvent themselves to survive: aristocrats become servants, priests become citizens, and revolutionaries become counter-revolutionaries. This shape-shifting necessity creates dynamic characters whose identities remain fluid throughout their stories.

The period’s social chaos meant that yesterday’s certainties became today’s death sentences. A character’s ability to read the political winds and adjust accordingly often determined their survival—much like a pirate captain navigating treacherous waters, though the stakes here involved losing one’s head rather than one’s ship.

Notable Authors and Their Revolutionary Masterpieces

Charles Dickens: The Master of Revolutionary Drama

No discussion of Revolutionary France historical fiction would be complete without acknowledging Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Published in 1859, this masterpiece established many conventions that continue to influence the genre today. Dickens’ famous opening—”It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”—perfectly captures the era’s contradictions.

Dickens masterfully weaves together the stories of Charles Darnay, the French aristocrat trying to escape his family’s bloody legacy, and Sydney Carton, the dissolute English lawyer who finds redemption through sacrifice. The novel’s exploration of resurrection and renewal against the backdrop of revolutionary violence remains as powerful today as when it first appeared.

The author’s portrayal of the revolutionary mob as a destructive force reflects Victorian anxieties about popular uprising, yet his sympathy for the oppressed masses prevents the work from becoming mere counter-revolutionary propaganda. This balanced approach allows modern readers to appreciate the complexity of revolutionary politics without taking sides.

Baroness Orczy: The Scarlet Pimpernel’s Enduring Appeal

Baroness Emmuska Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905) introduced one of literature’s most enduring heroes: Sir Percy Blakeney, the seemingly foppish English aristocrat who secretly rescues French nobles from the guillotine. The novel’s success spawned numerous sequels and established the template for the gentleman adventurer genre.

Orczy’s work appeals to readers who prefer their Revolutionary France historical fiction with a healthy dose of swashbuckling adventure. The Scarlet Pimpernel’s elaborate disguises, daring rescues, and witty repartee provide escapist entertainment while still acknowledging the period’s genuine horrors.

The character’s dual identity—effete dandy by day, heroic rescuer by night—reflects the era’s theme of hidden identities and social masquerade. In revolutionary France, everyone wore masks, whether literal or metaphorical, making the Pimpernel’s theatrical approach oddly appropriate.

Contemporary Voices in Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

Modern authors continue to find fresh angles on this well-explored period. Writers like Hilary Mantel and Kate Quinn have brought contemporary sensibilities to revolutionary narratives.

These authors often focus on previously overlooked perspectives: women’s experiences during the revolution, the stories of ordinary citizens caught in extraordinary circumstances, or the international implications of French revolutionary politics. Their work demonstrates that Revolutionary France historical fiction remains a vibrant and evolving genre.

The Historical Accuracy Debate

Balancing Entertainment with Education

Revolutionary France historical fiction faces the perpetual challenge of balancing historical accuracy with narrative entertainment. Readers expect authentic period details—the correct terminology, accurate social customs, and plausible historical scenarios—while also demanding compelling characters and engaging plots.

The most successful authors in this genre conduct extensive research, immersing themselves in primary sources, contemporary accounts, and scholarly works. They understand that authentic details enhance rather than burden their narratives. When a character mentions the price of bread in 1789 or references specific revolutionary newspapers, informed readers appreciate the accuracy while casual readers simply enjoy the verisimilitude.

However, historical fiction isn’t history—it’s fiction set in a historical period. Authors must sometimes prioritize dramatic necessity over strict accuracy, compressing timelines, combining historical figures, or placing fictional characters in real events. The key lies in maintaining the period’s essential spirit while crafting compelling stories.

Common Historical Misconceptions

Revolutionary France historical fiction sometimes perpetuates popular misconceptions about the period. Marie Antoinette probably never said “Let them eat cake” (the phrase predates her arrival in France), the guillotine was considered a humane form of execution, and most revolutionaries weren’t bloodthirsty monsters but ordinary people caught in extraordinary circumstances.

Responsible authors research beyond popular myths to uncover the period’s genuine complexity. They recognize that the revolution wasn’t simply a conflict between good and evil but a complicated struggle involving multiple factions with competing visions of France’s future.

The guillotine was invented for the French Revolution – Actually, similar devices existed for centuries before. Dr. Guillotin simply advocated for a more humane, egalitarian method of execution that was already being refined.

Everyone was starving before the Revolution – While food shortages existed, France wasn’t universally impoverished. Many regions were prosperous, and the crisis was more about unfair taxation and political representation than widespread famine.

Marie Antoinette said “Let them eat cake” – No historical evidence supports this quote. It was likely attributed to her decades later as anti-monarchist propaganda, possibly originating from Rousseau’s earlier writings about an unnamed princess.

The Revolution was entirely about class warfare between rich and poor – The reality was far more complex, with middle-class bourgeoisie, progressive nobles, and various urban and rural groups having different motivations and conflicts.

Robespierre was a bloodthirsty dictator from the start – He initially opposed the death penalty and evolved into his extreme positions gradually. His Reign of Terror lasted only about a year before he himself was executed.

Less Common Misconceptions

The Revolutionary Calendar was purely secular and rational – While it removed religious references, it was also deeply tied to agricultural cycles and contained its own quasi-mystical elements, including festivals celebrating abstract virtues like “Reason” and “Supreme Being.”

Women had no political power during the Revolution – Women like Olympe de Gouges wrote influential political treatises, women’s political clubs wielded significant influence, and female market vendors (the “poissardes”) were major political players who could make or break leaders.

The Revolution destroyed all French cultural traditions – Many revolutionary leaders were actually trying to create new traditions rather than eliminate culture entirely. They established museums, promoted arts, and tried to create secular ceremonies to replace religious ones.

Provincial France simply followed Paris’s lead – Many revolutionary ideas and movements actually originated in the provinces. Cities like Lyon, Marseille, and Bordeaux had their own revolutionary trajectories that sometimes conflicted with or preceded Parisian developments.

The Revolution was anti-intellectual and destroyed learning – While some libraries and institutions were damaged, the Revolution also established new schools, standardized weights and measures, founded the metric system, and created institutions like the École Polytechnique that advanced scientific learning.

Writing Revolutionary France Historical Fiction: Challenges and Opportunities

Research Challenges

Authors tackling Revolutionary France historical fiction face unique research challenges. The period’s political complexity requires understanding not just major events but also the intricate relationships between various revolutionary factions. The Girondins, Jacobins, Montagnards, and other groups each had distinct ideologies and goals that shifted throughout the revolutionary period.

Language presents another challenge. Revolutionary France introduced new terminology and concepts that modern readers might find unfamiliar. Authors must decide whether to use period-appropriate language (risking confusion) or modern equivalents (risking anachronism). The most successful writers find creative ways to explain historical concepts without disrupting narrative flow.

Social customs and daily life details require careful research. How did people dress, eat, and interact during different phases of the revolution? What were the practical implications of revolutionary changes for ordinary citizens? These details create authentic atmosphere while avoiding the dreaded “info-dump” that can bog down historical fiction.

Opportunities for Fresh Perspectives

Despite the genre’s popularity, Revolutionary France historical fiction still offers opportunities for fresh perspectives. Many stories focus on Paris and major political figures, leaving provincial experiences and ordinary citizens underexplored. The revolution’s impact on French colonies, religious communities, and ethnic minorities provides rich material for contemporary authors. The effects shortly after the Revolution are also not widely explored in historical fiction.

The period’s international dimensions also offer storytelling possibilities. How did the French Revolution affect other European nations? What was life like for French émigrés in London, Vienna, or America? These broader perspectives can provide unique angles on familiar events. I explore some of this in A Half Flower.

The Psychology of Revolutionary Characters

Moral Ambiguity and Character Development

Revolutionary France historical fiction excels at creating morally ambiguous characters whose motivations resist simple categorization. The period’s political fluidity meant that today’s hero could become tomorrow’s villain—or vice versa. This instability creates opportunities for complex character development that mirrors the era’s psychological turbulence.

Consider Maximilien Robespierre, the “Incorruptible” who became synonymous with the Terror’s excesses. Historical fiction can explore his transformation from idealistic lawyer to ruthless revolutionary, examining the psychological pressures that drove his evolution. Such character studies illuminate universal themes about power, corruption, and the price of political conviction.

A Half Flower

Two French boys witness the guillotine’s sharp edge on their way home from school. Years later, they’re running underground movements that cling to the Revolutions’s ideals, hearing still the metallic whisper. Shit hits the fan and our protagonist emigrates to an equally turbulent Kingdom: Hawai’i. Where French are illegal. But the island has got him in its grip.

Female characters in Revolutionary France historical fiction often navigate particularly complex moral terrain. The revolution offered unprecedented opportunities for women to participate in political life, yet traditional gender roles remained largely intact. Characters like Charlotte Corday, who assassinated Jean-Paul Marat, or Olympe de Gouges, who advocated for women’s rights, provide compelling subjects for fictional exploration. In A Half Flower, Balzac, student of medicine, and Jèrriais, former priest, discuss the role of women in society.

The Trauma of Revolutionary Violence

Revolutionary France historical fiction must grapple with the period’s extraordinary violence. The Terror claimed thousands of lives, while revolutionary wars devastated much of Europe. Authors face the challenge of acknowledging this violence without sensationalizing it.

The most effective approaches treat violence as a consequence of political and social pressures rather than gratuitous spectacle. Characters’ reactions to violence—whether as perpetrators, victims, or witnesses—reveal their moral character and psychological resilience. The period’s violence serves narrative purposes beyond mere shock value.

Revolutionary France vs. Other Historical Fiction Settings

Comparing Revolutionary Themes

Revolutionary France historical fiction shares thematic similarities with other turbulent historical periods. Like the American Revolution, English Civil War, or Russian Revolution, the French Revolution explores themes of political upheaval, social transformation, and individual survival amid chaos.

However, Revolutionary France offers unique elements that distinguish it from other revolutionary periods. The revolution’s radical social experimentation—including attempts to create new calendars, religions, and social structures—provides material unavailable in other settings. The period’s combination of Enlightenment rationalism and popular passion creates distinctive tensions.

The revolution’s cultural impact also sets it apart. Revolutionary France transformed European art, literature, fashion, and social customs in ways that continue to influence modern culture. This cultural dimension adds layers of meaning to historical fiction set during the period.

Maritime Adventures vs. Revolutionary Drama

For readers familiar with pirate historical fiction—those thrilling tales of maritime adventure and moral ambiguity—Revolutionary France historical fiction offers similar pleasures in a different setting. Both genres feature characters operating outside conventional social boundaries, whether as pirates challenging maritime law or revolutionaries overturning political order.

The moral complexity that makes pirate fiction compelling also drives Revolutionary France narratives. Just as pirates could be simultaneously criminals and folk heroes, revolutionaries embodied contradictory impulses toward liberation and destruction. Both settings allow authors to explore themes of freedom, justice, and the price of challenging established authority.

However, Revolutionary France historical fiction typically offers more opportunities for exploring class conflict and social transformation. While pirate stories focus on individual rebellion against authority, revolutionary narratives examine collective efforts to reshape entire societies.

Modern Relevance of Revolutionary France Historical Fiction

Contemporary Political Parallels

Revolutionary France historical fiction resonates with modern readers partly because the period’s political dynamics feel surprisingly contemporary. The revolution’s struggles with fake news (revolutionary pamphlets often contained wild exaggerations), political polarization, and the tension between security and liberty echo current debates.

The revolution’s use of political symbols, slogans, and mass media to shape public opinion prefigures modern political communication. Characters navigating this early form of information warfare face challenges that modern readers readily understand.

Social media’s role in contemporary political movements mirrors the revolutionary period’s pamphlet culture and political clubs. Both eras demonstrate how new communication technologies can rapidly mobilize popular opinion while also spreading misinformation and extremist ideologies.

The French Revolution coincided with and helped drive several revolutionary communication technologies:

Print Media Explosion

The most dramatic change was in print media. Prior to 1789, there were only a small number of heavily censored newspapers that needed a royal licence to operate, but the Estates General created an enormous demand for news, and over 130 newspapers appeared by the end of the year. Over the next decade, more than 2,000 newspapers were founded, 500 in Paris alone.

Between 1789 and 1799, over 1,300 new newspapers had emerged, combined with a large demand for pamphlets and periodical literature, which caused a flowering, albeit short-lived press. The scale was unprecedented – printers turned out many thousands of pamphlets and newspapers, sometimes as many as 10,000 to 12,000 copies of individual newspapers.

Thomas Carlyle famously called 1789-95 the ‘Age of Pamphlets’. After the National Assembly declared that everyone could express themselves freely, France exploded with a wave of pamphlet writing and reading.

The Optical Telegraph

Most remarkably, the French Revolution saw the invention of the optical telegraph or semaphore system by Claude Chappe. On 2 and 3 March 1791, Chappe tested an optical telegraph with a system of synchronized pendulums and a white and black optical panel between the cities of Brûlon and Parcé in the Loire region.

When the Chappe semaphore telegraph was introduced during the French Revolution, it revolutionized communications by dramatically reducing the length of time it took for messages to travel. In the Chappe system messages were encrypted and translated by semaphore signals built on the tops of towers miles apart. A telegrapher in the next tower would read the semaphore signals through a telescope and retransmit the message to the following tower.

The French Revolution was the largest media event since the days of the Reformation – it was a revolution of spontaneous mass movements, rousing speeches and public festivals, but especially a revolution of print media. These new communication technologies both facilitated and were accelerated by the revolutionary upheaval.

Universal Human Themes

Beyond political parallels, Revolutionary France historical fiction explores universal human themes that transcend historical periods. The tension between individual desires and collective needs, the corruption of noble ideals, and the human capacity for both heroism and cruelty remain relevant regardless of historical context.

The period’s examination of identity and social roles speaks to contemporary concerns about authenticity and self-definition. Revolutionary France forced individuals to constantly reinvent themselves, much as modern society requires ongoing personal and professional adaptation.

Conclusion

The cobblestones of revolutionary Paris may have long since been swept clean of their bloodstains, but the echoes of that tumultuous decade continue to reverberate through the pages of historical fiction. Like the revolution itself, these novels refuse to be contained within neat categories—they are simultaneously educational and entertaining, horrifying and hopeful, intimate and epic in scope.

Revolutionary France historical fiction offers modern readers something increasingly rare: the opportunity to grapple with moral complexity without easy answers. In an age of political polarization and social media soundbites, these novels remind us that history’s most transformative moments were shaped by ordinary people making extraordinary choices under impossible circumstances. Whether it’s Sydney Carton’s redemptive sacrifice or the Scarlet Pimpernel’s theatrical heroics, these characters embody the timeless struggle between individual conscience and collective action.

For those who’ve sailed with pirates through Caribbean waters or wandered the sultry streets of New Orleans, Revolutionary France offers a different but equally compelling adventure. Here, the treasure isn’t gold doubloons but the precious currency of human dignity, and the battles aren’t fought on rolling decks but in the drawing rooms and public squares where ideas clash with deadly consequences.

The revolution’s promise of liberté, égalité, fraternité remains as intoxicating today as it was in 1789—and just as elusive. Perhaps that’s why we continue to return to these stories, seeking in their pages the answers to questions that each generation must confront anew: How far should we go in pursuit of justice? When does noble idealism become dangerous fanaticism? And what price are we willing to pay for the freedom we claim to cherish?

As you close this exploration of Revolutionary France historical fiction, consider picking up one of these remarkable novels. Whether you choose Dickens’ masterful tragedy, Orczy’s swashbuckling adventure, or a contemporary author’s fresh perspective, you’ll find yourself transported to a world where every choice carried life-or-death consequences—and where the echoes of revolution still whisper their urgent questions to anyone brave enough to listen.

Vive la révolution—and long live the stories that keep its spirit alive.

Your next read.

Essential Revolutionary France Historical Fiction: Top Recommendations

Classic Foundations

Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos (1782): While technically pre-revolutionary, this epistolary masterpiece captures the decadent aristocratic society whose excesses would soon fuel revolutionary fervor. The moral corruption of the Marquise de Merteuil and Vicomte de Valmont embodies everything the revolutionaries would later condemn—making it essential reading for understanding the world the revolution sought to destroy.

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1859): The undisputed masterpiece of Revolutionary France fiction, Dickens weaves together the stories of Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton against the backdrop of revolutionary terror. His famous opening—”It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”—remains the perfect encapsulation of the era’s contradictions.

The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy (1905): Sir Percy Blakeney’s daring rescues of French aristocrats established the template for the gentleman adventurer genre. Orczy’s swashbuckling tale offers escapist entertainment while acknowledging the period’s genuine horrors.

Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini (1921): Sabatini’s tale of André-Louis Moreau—lawyer, politician, actor, and swordsman—captures the social tensions that exploded into revolution. His famous opening line, “He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad,” rivals Dickens for memorable impact while perfectly capturing the era’s absurdities.

Modern Masterpieces

A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel (1992): Mantel’s brilliant debut novel follows the intertwined lives of Robespierre, Danton, and Camille Desmoulins from their provincial beginnings to their revolutionary destinies. Her psychological insight transforms these historical figures into complex, breathing characters whose motivations feel startlingly contemporary.

The Glass-Blowers by Daphne du Maurier (1963): Du Maurier traces her own family history through the revolution, following the du Maurier glassblowing dynasty as they navigate the changing political landscape. Her intimate family saga demonstrates how ordinary artisans experienced the revolution’s upheavals, making the grand historical narrative deeply personal.

City of Darkness, City of Light by Marge Piercy (1996): Piercy focuses on six women during the revolution, including Olympe de Gouges and Charlotte Corday, offering perspectives often overlooked in traditional accounts. Her feminist lens reveals how the revolution’s promise of equality remained frustratingly elusive for half the population.

The Gods Will Have Blood by Anatole France (1912): This Nobel Prize winner’s novel follows Évariste Gamelin, an idealistic young painter who becomes a fanatical judge during the Terror. France’s masterful exploration of how noble ideals can corrupt remains chillingly relevant to anyone who’s witnessed political movements lose their way.

Orientation For Different Tastes

Romance Lovers:

Annette Vallon by James Tipton – The passionate, forbidden love affair between Wordsworth’s French mistress and the English poet, set against revolutionary chaos

Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos – Dangerous liaisons and seductive games among the decadent pre-revolutionary aristocracy

The School of Mirrors by Eva Stachniak – A Polish baroness navigating love and survival in the treacherous final days of Versailles

Adventure Seekers:

The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy – Daring rescues, elaborate disguises, and narrow escapes from the guillotine

Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini – Swashbuckling swordplay, theatrical adventures, and a hero who’s part lawyer, part actor, all trouble

The Way to the Lantern by Audrey Erskine Lindop – An English actor’s wit and cunning help him survive revolutionary Paris’s deadly intrigues

Literary Fiction Enthusiasts:

A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel – Masterful psychological portraits of Robespierre, Danton, and Desmoulins with profound insights into power and corruption

The Glass-Blowers by Daphne du Maurier – An intimate family saga that transforms grand historical events into deeply personal human drama

The Gods Will Have Blood by Anatole France – A Nobel laureate’s haunting exploration of how idealism transforms into fanaticism

History Buffs:

A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens – The definitive fictional account of revolutionary violence and social upheaval

City of Darkness, City of Light by Marge Piercy – Six women’s perspectives reveal overlooked aspects of revolutionary society and politics

Madame Tussaud by Michelle Moran – Unique historical viewpoint through the eyes of the woman who created death masks of guillotine victims

What is Revolutionary France historical fiction?

Revolutionary France historical fiction is a subgenre of historical novels set during the French Revolution (1789-1799). These books explore the political upheaval, social transformation, and human drama of this turbulent period through fictional characters and storylines. The genre combines historical accuracy with compelling narratives, featuring themes like moral ambiguity, class conflict, and the corruption of noble ideals.

What are the best Revolutionary France historical fiction books?

The essential reads include Charles Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities,” Baroness Orczy’s “The Scarlet Pimpernel,” and Hilary Mantel’s “A Place of Greater Safety.” Other excellent choices are “Les Liaisons Dangereuses” by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, “The Glass-Blowers” by Daphne du Maurier, and “Scaramouche” by Rafael Sabatini. These novels offer different perspectives on the revolutionary period, from swashbuckling adventure to psychological character studies.

Why is Revolutionary France popular in historical fiction?

Revolutionary France captivates readers because it offers everything historical fiction enthusiasts desire: political intrigue, romance amid chaos, and morally complex characters. The period’s contradictions—noble ideals descending into the Terror—create perfect dramatic tension. The revolution’s themes of freedom, justice, and the price of change remain relevant to modern readers, making these stories both educational and emotionally engaging.

What themes appear in Revolutionary France historical fiction?

Common themes include love during dangerous times, the corruption of idealistic movements, survival and adaptation, and the tension between individual conscience and collective action. These novels often explore how ordinary people navigate extraordinary circumstances, the price of political conviction, and the human capacity for both heroism and horror during times of social upheaval.

Is Revolutionary France historical fiction suitable for beginners?

Yes! Many Revolutionary France novels serve as excellent introductions to both the historical period and the genre. “A Tale of Two Cities” remains accessible despite its age, while “The Scarlet Pimpernel” offers adventure-focused entertainment. Modern authors like Michelle Moran (“Madame Tussaud”) write with contemporary readers in mind, making complex historical events understandable without sacrificing authenticity.

2 responses to “Revolutionary France in Historical Fiction: Surprising Facts You Need To Know”

-

Very insightful read—definitely bookmarking this site for future reference.

-

Thanks TyT! I appreciate it! 🙂

-

Leave a Reply