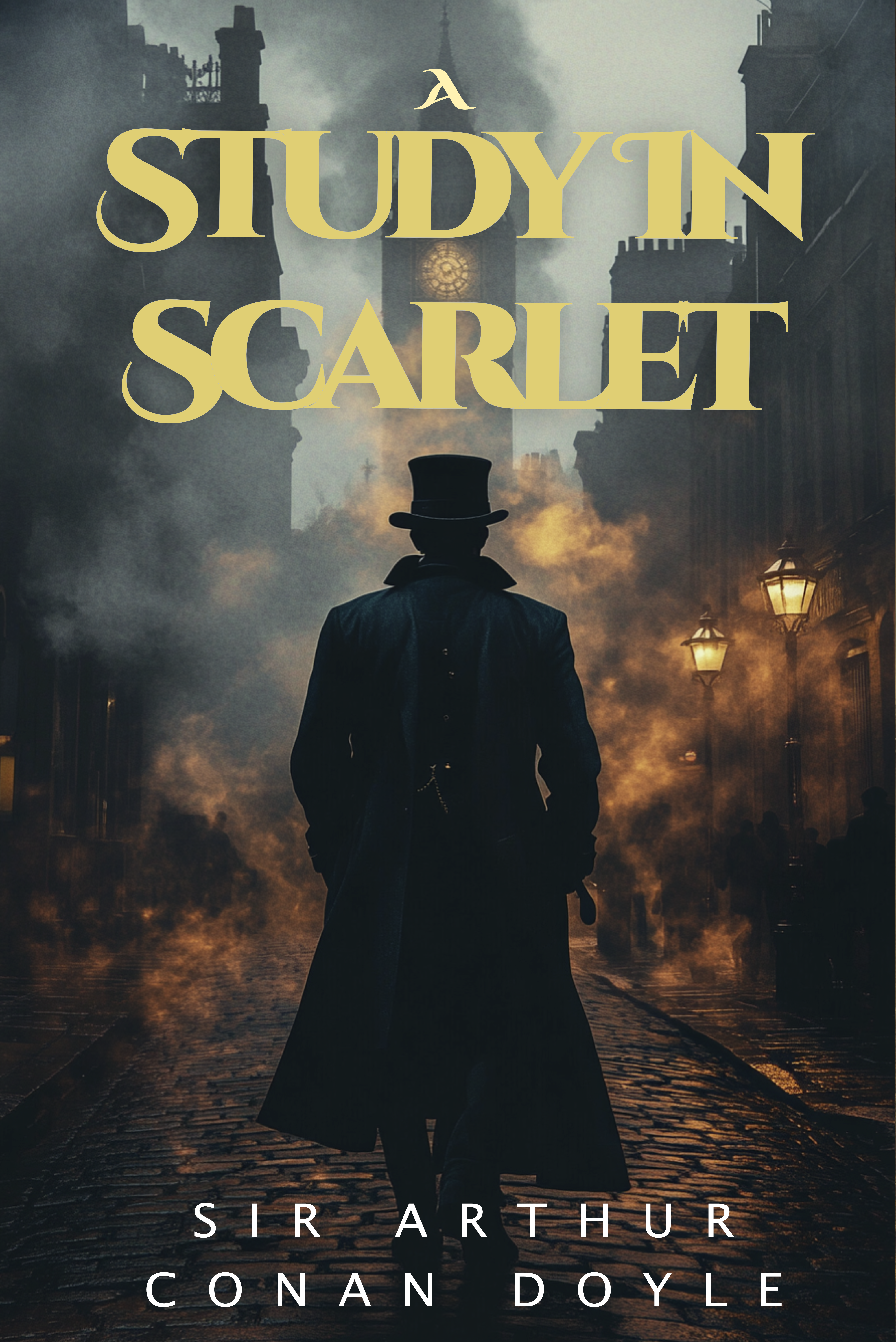

A Study in Scarlet (1887) was written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first published A Study in Scarlet (1887) in the Beeton’s Christmas Annual in December 1887. One may have difficulty believing that what would later become an iconic novelette and one of the best historical fiction series had a very slow start. Only when published in the Strand Magazine four years later in 1891 did the story gain its popularity. Then, Doyle became one founder of the modern criminal novel and model for detective novels. He was born on May 22 in 1859, and began his writing career in 1879. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, 1859, he died in 1930, Sussex, and was knighted in 1902 for his services during the South African (Boer) War.

For his character John H. Watson, M.D, late of the Army Medical Department, Doyle’s own studies and M.D. in 1882 gave him the insight for the renown vividness of his doctor narrator. The inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, consulting detective, came from one of Doyle’s professors, who displayed Sherlock’s type of analytical thinking, and doubtless also two earlier fictional characters, more on which later. In A Study in Scarlet, the duo embark on their first detective adventure, which introduces us to the extent of Sherlock Holmes’ analytical cleverness; a novelette to leave you in awe.

Synopsis of A Study in Scarlet

A Study in Scarlet is the first of the Sherlock Holmes books, so if you’re considering reading what I consider one of the best historical fiction series, this is the story to begin with. The plot of A Study in Scarlet is arguably inelegantly divided into two stories and separate parts. Let’s have a look at what this means.

A Study in Scarlet debuts with Dr. Watson, the narrator throughout the Sherlock Holmes series (with small exceptions to confirm the rule), introducing himself and explaining how he came to his unfortunate position. After a shot in the shoulder in Afghanistan and months of typhoid in Peshawar, our poor narrator is brought home to England to improve his health with eleven shillings and sixpence a day. In “the great wilderness of London” (ironically coming from someone who just returned from wars in then-India and Afghanistan), Dr. Watson soon realizes his allowance is not much.

So he looks for a roommate, which is how we’re introduced to Sherlock Holmes. Dr. Watson asserts he is too weak to bear much excitement or noise, and Mr. Holmes assures him, apart from the occasional violin playing, he is a quiet fellow. They move in together, and all seems fine. Until Mr. Holmes’ guest visits increase intolerably, and Dr. Watson is pushed into the confines of his room.

Dr. Watson grows curious about Sherlock Holmes, and due to his not being able to go out nor having many friends in London, grows obsessed with figuring out what “the deuce” Sherlock Holmes is up to. He even makes a list of his accomplishments to find a clue, but throws it into the fire, finding nothing useful. One morning at breakfast Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson discuss an article about the power of deduction, and when Dr. Watson declares it humbug, Mr. Holmes confesses he’s a consulting detective, the only one in the world, and that he wrote the article.

Wanna see the criminals’ side of things?

Jean Laffite: smuggler, pirate, and gentleman. Free for subscribers.

To prove his point, Mr. Holmes deduces information about a man standing across the street, who then comes up the stairs as the next client. Which is how Dr. Watson is drawn into the curious case of a dead man in an empty house. Dr. Watson is intrigued when he finds Mr. Holmes was correct in every deduction, and the reader realizes Dr. Watson is not as fragile after his war experiences as he assumed. He loses his limp.

Lestrade and Gregson, “the smartest of the Scotland Yarders,” await at the crime scene on Brixton road. Sherlock Holmes inspects the body, discovers “RACHE” written in blood on the wall, and the two official detectives give a report of their findings. Mr. Holmes smirks at their conclusions and wishes them luck on the scents they pursue.

Mr. Holmes pursues his own clues, uses the ring the detectives hadn’t noticed to entice the potential murderer by advertisement in the lost and found section, and is generally busy and gone for several days, much to the dismay of our narrator Dr. Watson, who is even more clueless than the detectives, but ever more intrigued by Sherlock Holmes.

Show spoiler

It’s yours for $1.00

Buy the annotated version with interesting information about places, outdated jobs mentioned, and much more.

Evaluation of A Study in Scarlet

Model for the genre of detective stories

The novelette A Study in Scarlet is the first story in the Sherlock Holmes series, which became, along with the earlier works – Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin stories and Émile Gaboriau’s Lecoq tales – the model for modern detective stories. The inciting incident of a new client, usually received in private chambers, which leads to ever more confusing clues which only the smart detective can unravel using analytical thought, climaxes with a chase, death, or both, to end with the conclusion of the detective’s success and sometimes his failure. This structure is iconic, and not without reason. A Study in Scarlet already follows this story structure. Still, the unexpected detour into Mormon life is challenging and not consistent with Doyle’s later Sherlock Holmes works.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was well aware of his predecessors and the expectation for this then-new genre. The narrator himself offers meta textual acknowledgement in an interesting comparison of Sherlock Holmes with Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin and shortly after Émile Gaboriau’s Lecoq:

“You remind me of Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin. I had no idea that such individuals did exist outside of stories.”

Which Sherlock Holmes does not take as a compliment, though he acknowledges the good intention. And later:

“‘Have you read Gaboriau’s works?’ I asked. ‘Does Lecoq come up to your idea of a detective?’”

Which also offends Mr. Holmes, for after some arguments of his own he answers, “It might be made a text-book for detectives to teach them what to avoid.”

So while A Study in Scarlet is a wobbly start into the detective genre due to its diversion into the American desert, with this debut the narrator promises readers a new, unique, and more analytical detective series than existed before. Doyle fully lives up to his promises, as both his success and the quality of the stories that follow in the Sherlock Holmes series attest.

Vivid characters, strong arc

A Study in Scarlet also offers character depth for the reader entering the Sherlock Holmes world, and Dr. Watson, the narrator, takes good time to introduce himself, his comrade Sherlock Holmes, and the others.

Sherlock Holmes is a purely analytical man, entrenched in the English Conservative Enlightenment of the 1800s where empirical philosophy (Watson actually mentions “philosophical tools” lying around in their flat), polite manners, and science were the values of a true enlightened gentleman. Doyle perfected this stereotype. The inspiration, Doyle reported, was one of his medical professors, though. His character does not change in this novelette, nor in the following stories.

Dr. Watson, on the other hand, has a satisfying character arc in A Study in Scarlet. He starts out somewhat depressed and considering himself fragile, and becomes an enthusiastic accomplice to the “amateur” detective Sherlock Holmes. This is most vividly shown in the fact that his limp disappears.

The official detectives don’t change. Lestrade is described “lean and ferret-like,” and Gregson as “flaxen-haired” and tall, and that they “have their knives into one another,” to the extent that they are “jealous as a pair of professional beauties.” They are portrayed as proud, ignorant in comparison to Sherlock Holmes, and as somewhat depraved for having no problem with taking the credit for Mr. Holmes’ work. The “scarlet thread of murder” ties all these characters together.

Twisty plot and morally challenging theme

A Study in Scarlet is not entirely plot-focused, nor only character-driven, which, according to Raymond Chandler, a fellow detective story author, is essential for this genre. He defines the perfect story model as an “adventure in search of a hidden truth,” and therefore gives rigid demands to theme.

Show spoiler

The narrator in The Honour of the Flag, for example, tries to achieve a similar effect by relying on court decisions, but, unlike the narrator in A Study in Scarlet, does not gain the modern reader’s sympathy for the evil doer. The deviation does impact pacing, though.

Interrupted pace

The excellently quickening pace in A Study in Scarlet is sadly halted when the narrator turns from first person to omnipresent, distant third person and we’re thrown into a desert on another continent twenty years before the murder. As the names of the murderer and victim appear, the pace slowly picks up again. It is fully back on track when we return to the murder story at the end of part two.

A Study in Scarlet (1887) contains humorous prose

In A Study in Scarlet, the image-filled prose, fledged with small archaisms, a tad of dialect, and truly historical world views, sparkles with humor. With the interactions between strong characters, the narrator manages to make us smirk almost on every page while the story unfolds in London.

For example, when the police officers meet with Sherlock Holmes, they invariably display their incompetence to him, and he rubs it under their noses:

“’I have left everything untouched.’ [Gregson]

‘Except that!’ my friend answered, pointing at the pathway. ‘If a herd of buffaloes had passed along there could not be a greater mess.’”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in A Study in Scarlet

Later on, Sherlock Holmes lets the officer pair Gregson and Lestrade loose on their hot scents, knowing they will return with more questions and fewer answers, and when he listens to each of their report, for they come to tell him proudly, Sherlock says he considers his news quite exciting, and yawns. It is also humorous how much detail the officers remark on, as if trying to impress Sherlock, and with this only show the reader how far off the track they have gone.

The narrator sometimes also uses humorous characterizations such as when he describes Lestrade as “lean and ferret-like as ever,” which does not distract from serving as a vivid and necessary characterization. The narrator is, however, also a man of his time when he attributes physical appearance as giving clues to character. It was a popular belief in the nineteenth century, and the narrator has this view when he describes Sherlock Holmes’ physical appearance:

“His eyes were sharp and piercing, save during those intervals of torpor to which I have alluded [opium]; and his thin, hawk-like nose gave his whole expression an air of alertness and decision. His chin, too, had the prominence and squareness which mark the man of determination.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in A Study in Scarlet

This truly historical world view shows even more when Sherlock Holmes uses his skills of deduction to discover the work of the man standing across the street:

“‘He was a man with some amount of self-importance and a certain air of command. You must have observed the way in which he held his head and swung his cane. A steady, respectable, middle-aged man, too, on the face of him—all facts which led me to believe that he had been a sergeant.’”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in A Study in Scarlet

It may be true that a man’s work was easier to discern back then, but it still seems unrealistic to a modern reader. Many jobs common at the time of penning have been lost, such as Boot (British, dated: a person employed in a hotel to clean boots and shoes, Oxford Dictionary of English), milk boy, or the racist “street Arabs” Sherlock employs, among other lost occupations. This truly historical world view is underscored with archaisms and dialect, much out of use nowadays in fiction. For example, we would not describe people lingering on the street as “loafers,” or describe someone as “dumbfoundered,” though it would surprise us to read someone “Ain’t afeared,” or hear an exclamation of “The last ink,” when someone solves a case. But these expressions also paint a historical picture and add to the vividness.

Doyle’s imagery also adds to the vividness of his prose. For example, when Mr. Holmes and Dr. Watson discuss Darwin’s theory, relatively young back then:

“There are vague memories in our souls of those misty centuries when the world was in its childhood.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in A Study in Scarlet

The most prominent and entertaining of Doyle’s narrative features, and which has captured readers for centuries, is his subtle and universal humor. A consulting detective didn’t exist back then, nor does it now, and no official detective would be happy to feel himself forced to consult an “amateur.”

A Study in Scarlet has thoughtful impact

Upon finishing the novelette A Study in Scarlet I was moved to thinking. Where do I draw the line for sympathy with a murderer? Why was I happy someone I sympathized with died of heart failure? Was the Mormon way of life portrayed biased? Could there be some good to it?

A Study in Scarlet (1887) is a recommendable historical fiction novelette

I would definitely recommend A Study in Scarlet to friends. I would warn them about the confusion they might experience at the beginning of part two, but I would tell them to continue reading because the ending makes up for it.

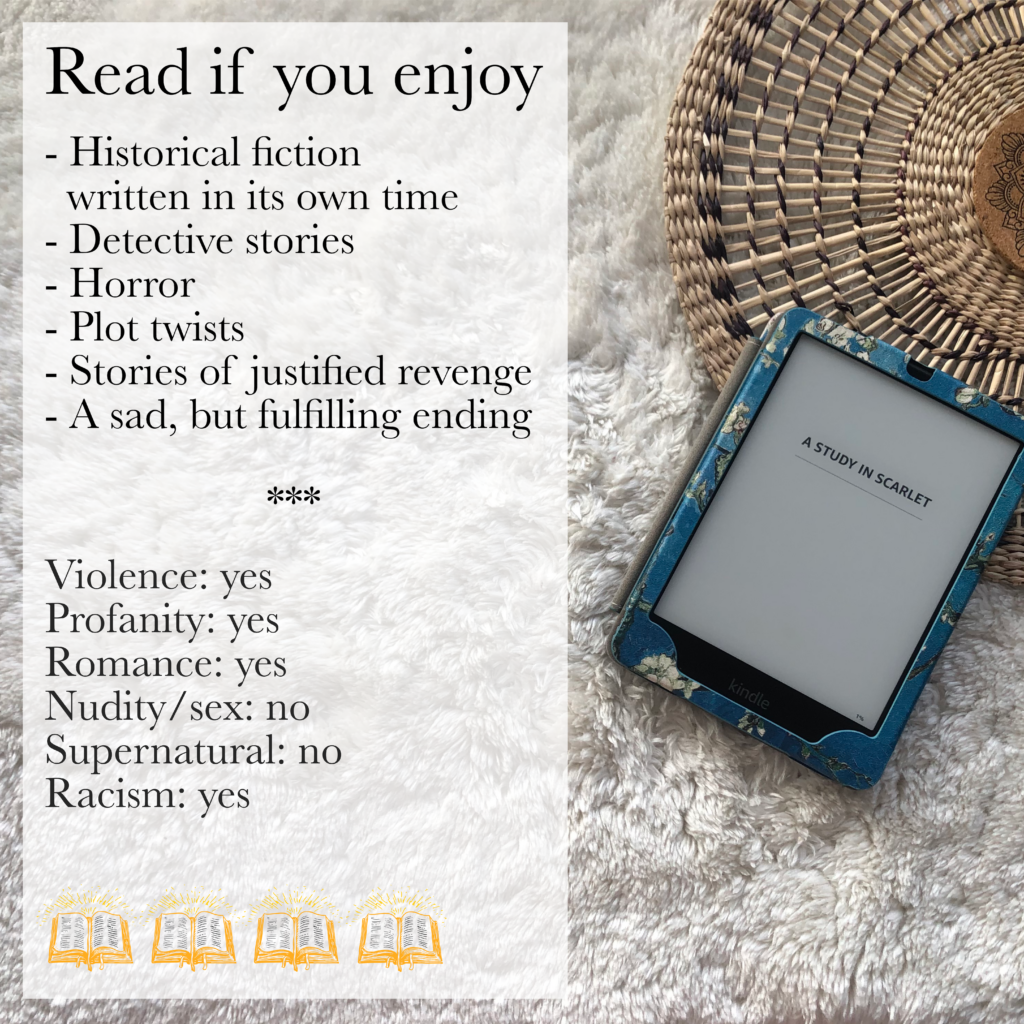

Golden Books Rating of A Study in Scarlet

Four of five Golden Books for A Study in Scarlet by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Violence

Yes

Profanity

Yes

Romance

Yes

Nudity/sex

No

Supernatural

No

Racism

Yes

The only drawback in A Study in Scarlet is the (necessary) deviation in part two.

Sources

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: A Study in Scarlet.

- https://conandoyleestate.com/news/on-this-day-in-history-arthur-conan-doyles-a-study-in-scarlet-was-first-published#:~:text=A%20Study%20in%20Scarlet%20is,Beeton%27s%20Christmas%20Annual%20in%201887 (see for an interesting photo of Doyle’s notes on Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Scarlet).

- PAGE, ANTHONY. “RATIONAL DISSENT, ENLIGHTENMENT, AND ABOLITION OF THE BRITISH SLAVE TRADE.” The Historical Journal, vol. 54, no. 3, 2011, pp. 741–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23017270. Accessed 19 Dec. 2023.

- Irwin, John T. “Mysteries We Reread, Mysteries of Rereading: Poe, Borges, and the Analytic Detective Story; Also Lacan, Derrida, and Johnson.” MLN, vol. 101, no. 5, 1986, pp. 1168–215. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2905715. Accessed 19 Dec. 2023.

FAQ

When was A Study in Scarlet published?

1887.

What series is A Study in Scarlet part of?

A Study in Scarlet is part of the Sherlock Holmes series, one of the best historical fiction series of all time. It is the first book; a novelette.

How long is A Study in Scarlet?

A Study in Scarlet is a novelette consisting of approximately 43,600 words (a regular novel has about 60,000 words). A Study in Scarlet takes about two and a half hours to read.

What genre is A Study in Scarlet?

A Study in Scarlet belongs in the detective story genre and is historical fiction written in its own time.

What is the theme of A Study in Scarlet?

A Study in Scarlet explores the morality of murder and revenge, the triumph of analytical thinking (reverse logic) over normal thinking, and death.

Who should read A Study in Scarlet?

If you enjoy historical fiction written in its own time, can stomach a few archaic expressions, enjoy worldviews deeply set in historical times, and are not put off by enriching diversions, A Study in Scarlet is perfect for you.

Like what you’re reading? Share it!

This is going to be incredibly useful for my work.

Thank you Blogi Nauki, I appreciate it! 🙂

Reading this piece felt like walking through a beautiful garden of ideas — each thought more inviting than the last.

Thanks TyT! I appreciate it! 🙂

Very insightful read—definitely bookmarking this site for future reference.

Leave a Reply